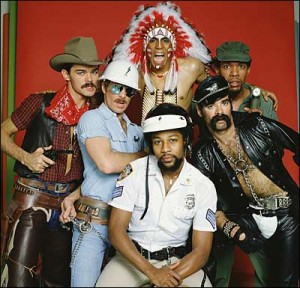

The next time you download the perennial disco classic “Y.M.C.A.,” by the Village People, for your high school reunion or wedding reception, many of the royalties could be going to a different place than they are now. That is, to the Village People instead of their record company.

Recently, we discussed a clause in the United States Copyright Act of 1976 granting artists “termination rights” after a work has been published for 35 years, as long as they make a claim for these rights within two years before the deadline. Since the first deadline is 2013 (the act didn’t go into effect until 1978), many artists are scrambling to stake their claim in gaining copyrights to their work that have thus far belonged to record companies. However, since this promises to produce a string of high-profile legal cases, artists and record labels have been quiet about their plans so far.

Until now.

Victor Willis, lead singer of the Village People, has exercised his right of termination for not only “Y.M.C.A.,” but also of 32 other Village People songs that he co-wrote. Already, the publishing companies that administer the rights to the songs, Scorpio Music and Can’t Stop Now Productions, have asked a Los Angeles judge to disallow Willis’ claim, as they say the singer was an employee under a “writer for hire” agreement.

Under the Copyright Act, this would mean that Willis acted as an employee of the record company, thereby naming the record companies as the “author” of the work. In this case, Willis would not be able to exercise termination rights.

Though no decision has yet been made, this could set the precedent in many of the cases that will arise as artists fight for the right to control their body of work.

The New York Times, who first reported this story, quoted a spokeswoman for Willis as saying that the singer currently earns $30,000 to $40,000 from Village People recordings, but that if he gains termination rights the number could triple or quadruple.

This is one of the first mentions of how much money is actually at stake between the artists and the record companies. It seems the “work made for hire” clause is going to be at the center of the debate, and most likely will be judged individually for some complex record company contracts that were signed at the time.

The precedent could affect cases for recordings made every year after 1978 as they too become eligible for termination rights.